Exactly 5 months ago, sometime around 2am German time, my father tried to sit up in his home-version of a hospital bed, supported by his wife of many decades, tried to clear his throat, failed, sank back, and never breathed again.

He finished a life of 78 years, a remarkable feat considering his many health problems, worsened, if not caused by his voracious consumption of ethanol in various forms. He began this habit with ever increasing passion after his GP encouraged him in his thirties, post-kidney-stone, to down a regular measure of beer to somehow help with the flow of things.

He was born in 1940, lost his father before the war was over through an execution ordered by court martial in Poland, and then lost his mother to cancer less than 15 years later.

It doubtlessly was not an easy childhood. Both him and my mother provided me with a seemingly infinitely more protected one, even though closer inspection would show you significant fractures in that, too.

His passing, as expected as it was after a steady and yet rapid decline of six months, started a very sudden series of utterly unexpected familial developments and discoveries, and I will possibly never fully understand how much these were responsible for a turmoil and confusion, and bitterly deep sense of grief I have been feeling since then.

Grief over filial loss feels like being a member of an exclusive club, similar to other “special experiences” in life like parenting, taking ballet class, renal colics, moving to a foreign country: You feel that you can really only talk to people in a meaningful way, who have made similar experiences.

One of my most precious moments in the weeks after my father’s death was an unexpected conversation over lunch with a friend in London, who had also lost her father, even though it was already quite a number of years ago.

The pain never stops, she said. And so far, she seems proven right. It was comforting to speak to someone who knew instinctively, who felt what I felt, whose expression of condolence seemed so very much more powerful than those well-intended ones from friends and others, who had not yet lost a parent.

And still.

Every experience is unique.

And yet.

It is reassuring to hear that there are common things, that connect us.

Very importantly, too, I am far from saying that losing a parent in the middle of your life is the worst that can happen to you. It really is not. Losing a child surely must be on a whole other level of grief, another dimension.

Grief makes us realise the complexity of the relationship we had with the person we have lost. Invariably, this newly discovered complexity falls into the vacuum created by the death of the person we had this relationship with.

No meaningful adjustments are possible anymore. Or are they?

Yes, death is final. It is a brutal cut between being and not being. Or, if you believe in an afterlife, between being here and being there. No, I have no inclination to complicate the matter further by blurring this line with ghosts or other ideas of communication between these two states.

However, like so many other things that were not of much use to me before, I now really relate to the idea of “he lives on in you”.

Nature and nurture. We inherit our parents’ genes, but they also shape us in so very many other ways. As Philip Larkin phrased it so beautifully, “They fill you with the faults they had and add some extra, just for you.” But they also give you great gifts of passions, interests, insights.

My father loved England. He loved Shakespeare. He loved classical music. Anyone who knows me, will instantly recognise these three characteristics as essential to who I am.

My mother loves people. She has a never-ending passion for kindness.

I consider myself very lucky to have had such parents, even though they did come with their own faults, of course.

Hans Mittelmaier, he was a very intelligent, hard working man. He had a gift of being able to talk to anyone regardless of background and education. However, he failed to treat those closest to him with the love and respect that he so very much demanded from them. Love and respect, dad, they can never be one-way streets. It breaks my heart that you never were able to fully understand that and adjust. It made you so very, very lonely.

And yet, he was and is an inspiration to me. One of the last intellectual efforts he indulged in, was to learn Hebrew and Arabic. I never asked him why. I do remember that he told me with deep sorrow about having forgotten it all again once his dementia started to eat away at what had always been so very important to him, his brain.

Dad, the value of a person cannot be measured in how clever they are. Our value, I believe this deeply, comes from how we treat others. Thank you, mum.

You are dead now. I do not need to argue with you anymore. I do not need to justify myself, I do not need to try to help you heal wounds that you never had a chance to heal. What I can do is honour the riches you have given me, develop them further, and stay wary of the weaknesses that troubled you so much.

Our parents live on in us, it is up to us, how we accommodate them. We can strengthen the good in our memories, without forgetting the bad.

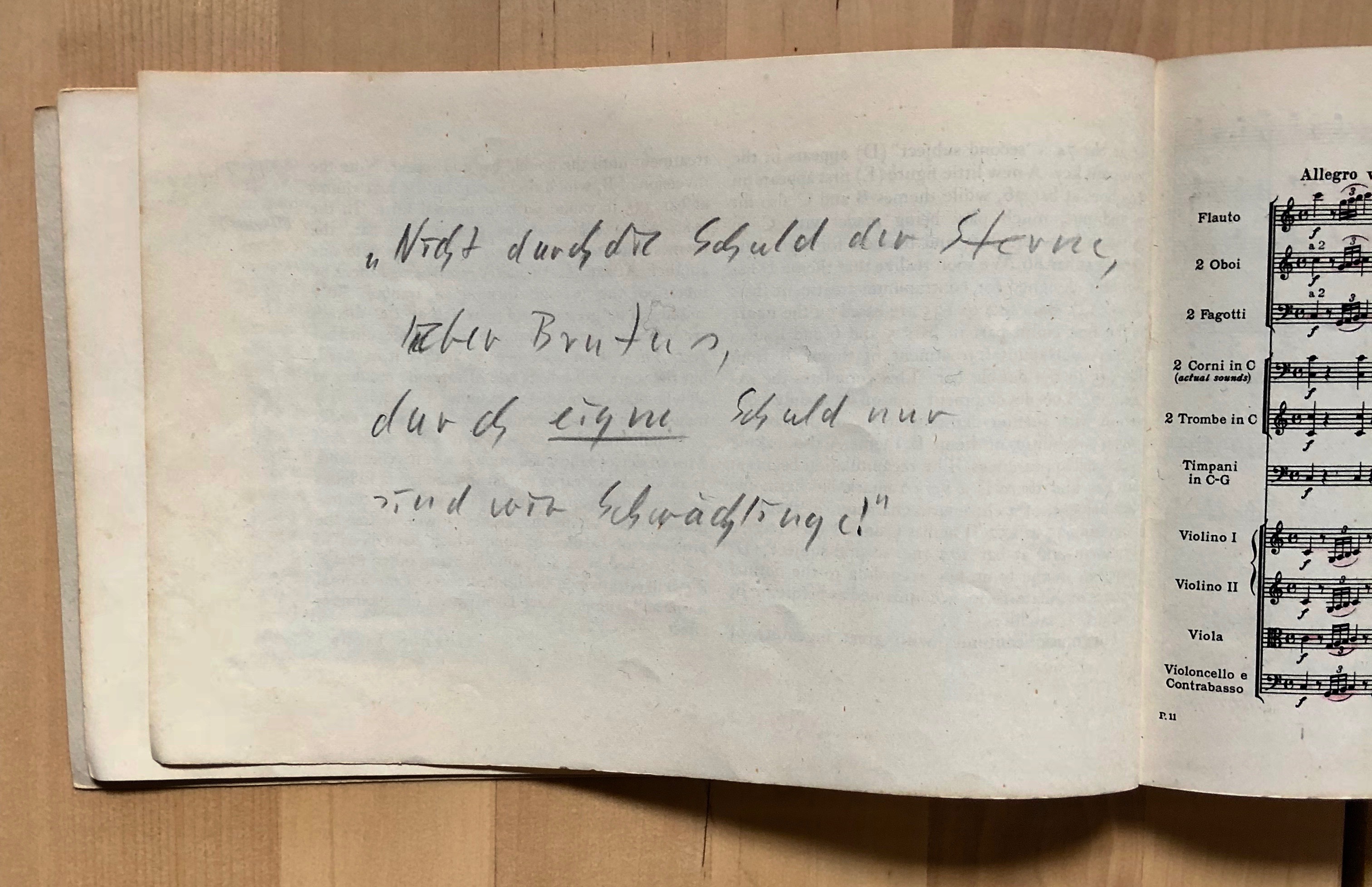

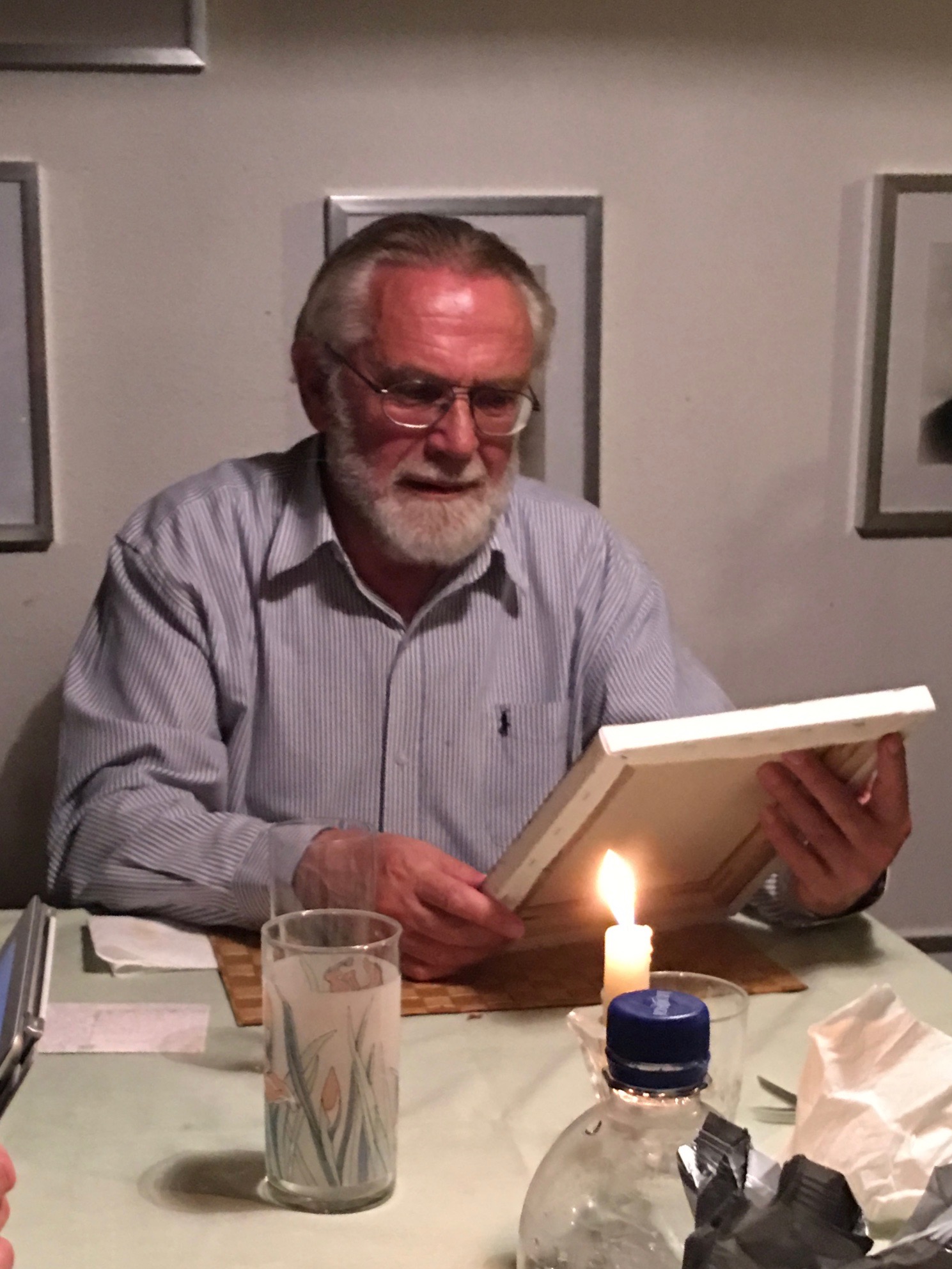

It is not in our stars, dear Brutus, it is in ourselves that we are underlings. My father aptly quoted Shakespeare in his score of Mozart’s Jupiter symphony. It now is one of my dearest possessions, while it made me angry in my turbulent youth.

I will try to honour his memory in an honest, but heartfelt way. He strived and struggled. I will try to find strength in the knowledge that his was an eager, curious, powerful brain, and I will try to always heed the warning that the loneliness of his life put into a nutshell: Be good to those who are good to you and you will never be truly alone.

He lives on in me. I will create him a comfortable and peaceful study in my heart, where he can rest in peace and yet have his eyes on what goes on in my world, not troubled any longer by those puzzles he found impossible to solve.

Requiem aeternam dona eis.

الله يرحمه

ינוח על משכבו בשלום

May the flying spaghetti monster provide him with eternal tomato sauce.